Dion

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

(The River Thames at Battersea, Queenhithe and Kingsnorth Powerstations), 2007

Unique artwork

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

Mark Dion

Fieldwork IV

Over the past thirty years, the artist has studied the relationship between nature and culture, drawing on the classification system and museology.

Fieldwork IV blurs the boundary between scientific and artistic working methods.

The artist took samples from different natural environments in London, each reflecting both the current situation and historical aspects of the capital. Assuming the guise and methods of a scientist, the artist proposes a point of view that questions the way in which man, through science, gives meaning to the natural world.

Fieldwork IV was created in 2007 for the British Museum of Natural History in London, to mark the tercentenary of the birth of Linnaeus, the Swedish botanist who introduced the concept of biodiversity and the classification of living organisms. The installation is part of Systema Metropolis, a four-part series of exhibitions that enabled the artist to carry out a systemic exploration of the banks of the Thames, the long river that flows through the city of London before joining the North Sea.

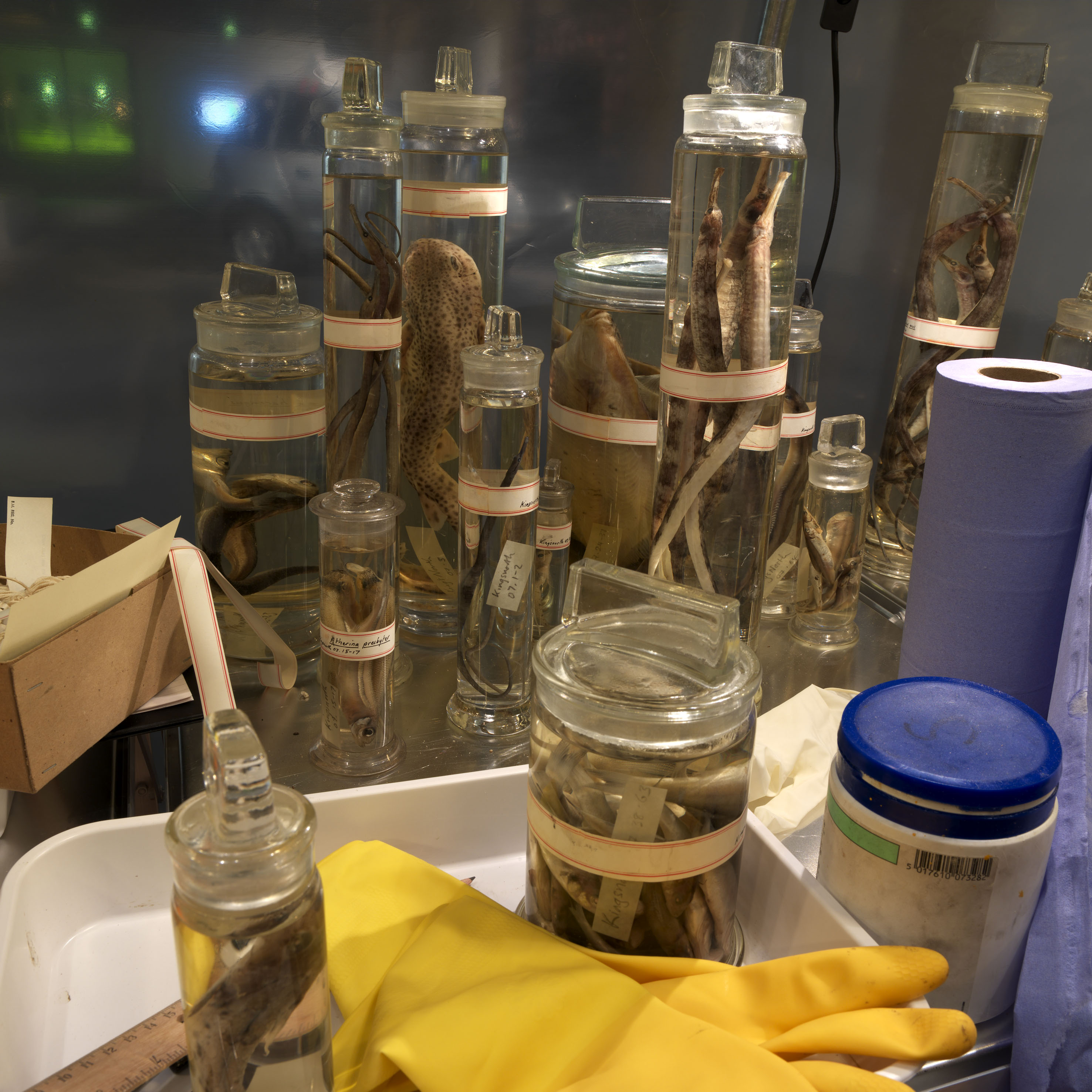

In Fieldwork IV, roughly organized by typology, this mass of objects awaits future, more systematic classification within a large greenhouse. This appears to be a scientific laboratory, where the equipment and tools used for the work seem to have just been laid out, ready for use. Visible from the entrance, alongside the detritus of daily activities, a number of more or less rare fish (including the only example of a seahorse found in the Thames) are preserved like specimens in formalin.

Showing the intermediate stage between collection and systematized categorization, this installation questions the authority and validity of scientifically accepted selection and classification criteria, reminding us that the development of knowledge also reflects a society's self-awareness.

The result that is laid in front of us, this compilation of findings, allows us to grasp a single place from natural, cultural, economic and spiritual perspectives.

The impossibility of accessing the inside of this "laboratory" gives us the impression of being confronted with a scientific device, access to which is exclusively reserved for the personnel in charge. As the visitor's vision is filtered by the polyester tarpaulin, a halo of mystery remains. It highlights the gap between the work of scientists and the idea of it in the collective imagination. For Mark Dion, moreover, "if the work is enigmatic, it allows the viewer to play an active role", bringing out the human dimension, with its doubts and uncertainties.

"Working with situations rather than mere object making, Mark Dion transforms the white cube into a skilful interweaving of temporalities" (Natacha Pugnet).

By placing the ancient and the modern on the same level of reception, Dion attributes the same interest to recent lifestyles as to those of the past. The continuous flow of the river, which crosses lands and eras, re-establishes equality between things, eliminating the hierarchy between valuable and everyday objects, between relics, archaeological artefacts and garbage.

In this way, Fieldwork IV shows us how every object, regardless of its era, is the product of the same human process, from production to rejection, from rediscovery by archaeologists to scientific interpretation. The invisible, perpetual action of the river thus becomes the receptacle of our civilization: it brings to the surface the vestiges of the past, while questioning us about our future.

Indeed, one question arises: will the objects that emerge from our present activity constitute an archaeological reality in the future?

What should be preserved and how?

What does their classification tell us?

With characteristic humor and an interdisciplinary approach, Mark Dion stands, as he puts it, "in the shadow" of scientific methods to deconstruct their mythologies. He questions the principles that have established the foundations of our knowledge, and how humans, by means of science, attempt to become aware of the world around them. It is in this perspective that Fieldwork IV enters into a relationship with the Museums' exhibition rooms, in which the dialogue between art and science, between ancient and contemporary works, echoes the questions raised by Mark Dion's work.