12 755 000 000 jours

12 755 000 000 jours

12 755 000 000 jours

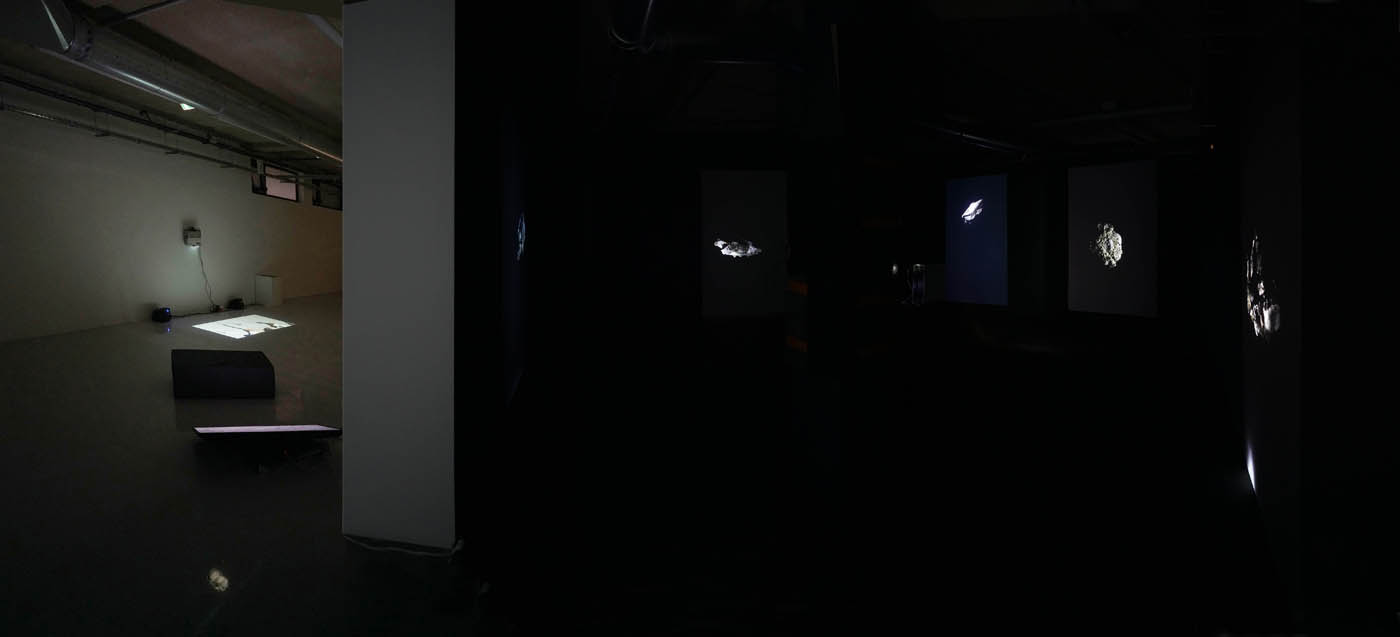

Vue d'exposition

12 755 000 000 jours

Vue d'exposition

12 755 000 000 jours

Vue d'exposition

12 755 000 000 jours

Vue d'exposition

12 755 000 000 jours

Vue d'exposition

12 755 000 000 jours

Vue d'exposition

OPENING ON SUNDAY JANUARY 15TH, FROM 2PM TO 6 PM

12 755 000 000 jours

For over 10 years I have been searching for primeval mammals in the Oligocene se- diments of Wyoming. Few things have touched me as much as those summer weeks each year. But for a long time I could not integrate fossils directly into my artistic work. This despite the fact that fossils are in many ways very similar to paintings, and despite the fact that I believe I seek out fossils for the same motivations that led me to become an artist. I have tried and tried. It has never worked. If you take a human skull, you have a metaphor; death, transience, fears; all kinds of meanings present themselves. But the skull of a primeval horse? It remains what it is: the skull of a primeval horse.

The sediments I am searching in were deposited about 35 million years ago during the transition from the Eocene to the Oligocene. What was then a forested, moist habitat with mild temperatures is now an extremely hot and dry landscape. You hike through canyons that crisscross the land, looking for the slightly lighter white of fossilized bones and skulls peeking out from the walls. It?s hard work to bring them to light. Searching, finding and preparing fossils is a lot like making a painting.

Then came the pandemic. For two years, I could not come to the United States. I looked at the many thousands of photos from Wyoming. Over and over again. In the second year, I began to translate my longing into work. I was looking for some kind of essence of my experiences there. I wanted to translate the imagery of fossils into the structure of watercolors. Fossils are often flattened. Like a painting. Or spatial like a sculpture. They deposit randomly, but that randomness leads to en- viably good compositions. Parts can disintegrate, be displaced, distorted, cut off. A fossil is the trace of the last moments of a living being. A trace that can be read. Like a picture. I painted and drew my photos of looking for fossils as if they were settling into a sediment. As if my memories were being embedded. But it is not about telling stories. Pictures do not tell stories. They show moments.

What does it mean to dig into the ground? Into the texture of a place, its history? One might think that this is mainly changing the place. But the holes I dig disappear in 1, 2 years. Quite different from the touch that searching has left in me.

Martin Dammann